Classical Chinese 101 (Part 2)

In the first Classical Chinese 101 blog, we went over some of the more technical aspects of classical Chinese, both historically and linguistically. There are definitely some arguments to be made against classical Chinese in terms of clarity—it’s easy to misinterpret and difficult to decipher, if you don’t already have a strong linguistic foundation and a good deal of historical knowledge.

But despite these challenges, classical Chinese served as the de facto written language for thousands of years. And not only in China, but in other East Asian countries as well.

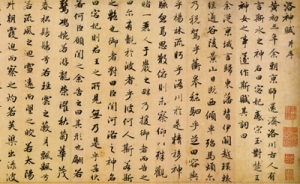

[Caption: A memorial to fallen warriors, written in classical Chinese, found in Kenroku-en, one of the “Three Great Gardens of Japan.”]

So what was the reason for its widespread use and lasting popularity? Some claim it was due to China’s huge historical influence over Southeast Asia. Others say it was because of its efficient use of writing space, since composing documents on bamboo strips required carving. Even when paper became available, its scarcity also encouraged the use of a more compact writing style. Classical Chinese was just the perfect choice for the scholar or official looking to say more with less. Plus, there was a bonus—in classical Chinese, there’s no punctuation needed when writing—commas question marks and periods are all implied so they’re not explicitly written. That is very convenient right?

While the above may be true, I have my own explanation. China, with its dozens of ethnic groups and hundreds of spoken dialects, managed to unify written language in such a way that not only speakers of Mandarin and Cantonese, but also speakers of Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese could all write to each other and understand one another without a single shared pronunciation. And they were able to do so all the way until the beginning of the 20th century.

To help illustrate, I’ve chosen a short article of classical Chinese text written by the poet-philosopher Liu Yuxi (772-842 C.E.) during the Tang Dynasty. It’s called “Humble Dwelling Inscription” (陋室銘). It reads:

山不在高,有仙則名。The mountain needs not be tall; if it is home to a saint, it will be famous.

水不在深,有龍則靈。

The waters need not be deep; if they are home to a dragon, they will be magical.斯是陋室,惟吾德馨。

A crude and simple dwelling this would be, if not for my virtues.苔痕上階綠,草色入廉青。

Moss grows green on the steps; the grass shines verdant into the room.談笑有鴻儒,往來無白丁。

Great scholars talk and laugh within; no unlearned ones pass through here.可以調素琴,閱金經。

One can play upon the simple zither, or peruse the golden scriptures.無絲竹之亂耳,無案牘之勞形。

There is no chaotic music to muddy the ear, no official document to bring forth hardship.南陽諸葛廬,西蜀子雲亭。

Like the grass hut of Zhuge Liang in Nanyang, the pavilion of Ziyun in West Shu.孔子雲:“何陋之有?”

As Confucius said, “How could one call it unadorned?”

This passage was composed after Liu’s demotion from palace officer to a small village official. Facing the challenges of poverty and public humiliation, he had this passage carved onto a stone slab outside his cabin. The entire text consists of only eighty-one characters, yet it still paints a vivid scene, satirizes villains for their arrogance, and conveys the moral values he cherished.

I like to think that classical Chinese was so widely adopted because it is simply such a beautiful language, an elegant and refined language, a language that conveys deep meanings, complex ideas, and emotional intensity. It is a language that manages to be both beautifully humble and unequivocally poetic.

Jeff Shao

Contributing writer